We started early from Bodh Gaya, hired a cab, and set out towards Nalanda. The drive is about 90 kilometres and, for the most part, quite beautiful. Long stretches of highway slowly give way to villages, fields, gentle hills, and winding roads that feel unhurried—almost preparing you mentally for what lies ahead.

On the way, we passed through Rajgir, a small hill town nestled among forested slopes. The driver pointed out a few spots—safaris, ropeways, viewpoints—and suggested we explore them. We decided to push on to Nalanda first and see later if we had the energy while returning.

Nalanda was the real reason we were here.

A University Before Universities Existed

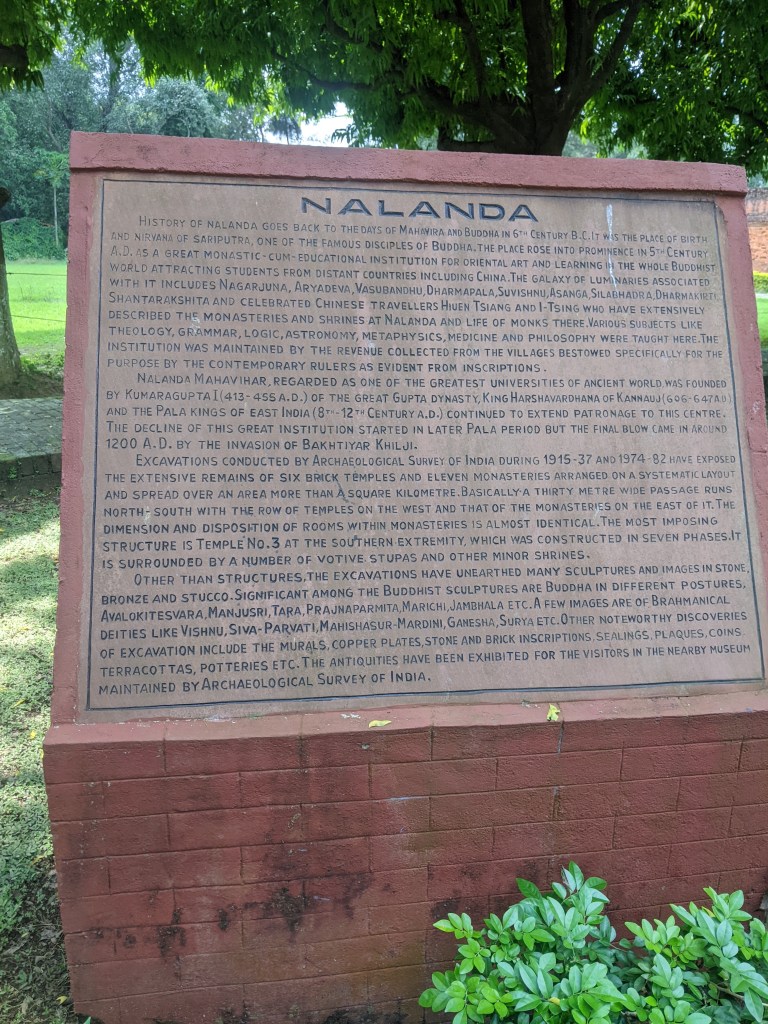

Nalanda is not just another historical site. It is widely regarded as the world’s first great residential university, a place that attracted students from across Asia—China, Korea, Japan, Tibet, Sri Lanka, Southeast Asia—long before Europe even conceived of universities.

At its peak, Nalanda is believed to have housed around 10,000 students and teachers and a library so vast that ancient accounts speak of millions of manuscripts. What struck me most while reading about it—and later, while walking through it—is that Nalanda wasn’t limited to religious instruction alone.

Yes, Buddhism was at its core. But alongside it flourished studies in mathematics, astronomy, logic, grammar, medicine (Ayurveda), metaphysics, philosophy, and cosmology. This was a true multidisciplinary center of learning—an ancient Ivy League, centuries before the term existed. Aryabhatta, a stalwart of early mathematics was a teacher here in Nalanda.

What’s even more fascinating is that Nalanda’s intellectual roots stretch back much earlier than its formal establishment as a university. As a seat of learning, this place had been active since at least the 6th century BCE, gradually evolving into the Mahavihara that history remembers.

Repeated Attacks, Repeated Rebuilding

Nalanda’s story is also one of resilience—and eventually, tragedy.

It was attacked more than once.

- The first major attack came from the Huna ruler Mihirkula, invaders from outside the subcontinent. The intent was largely plunder and destruction. Nalanda suffered damage—but it was rebuilt, supported by rulers who understood its value.

- The second attack, attributed to a Gauda (Bengal) king, is believed to have been driven more by religious antagonism. Again, Nalanda was damaged—but again, it rose back.

- The final blow came in the late 12th century, led by Bakhtiyar Khilji.

This time, Nalanda never recovered.

Accounts say the invaders set fire to the libraries, and the blaze burned for months—some say three months. Try to pause and imagine that for a moment. A library so vast, so densely packed with knowledge, that it could burn continuously for months.

Entire civilizations’ worth of learning—on science, medicine, philosophy, astronomy—simply turned to ash.

Walking Through Silence

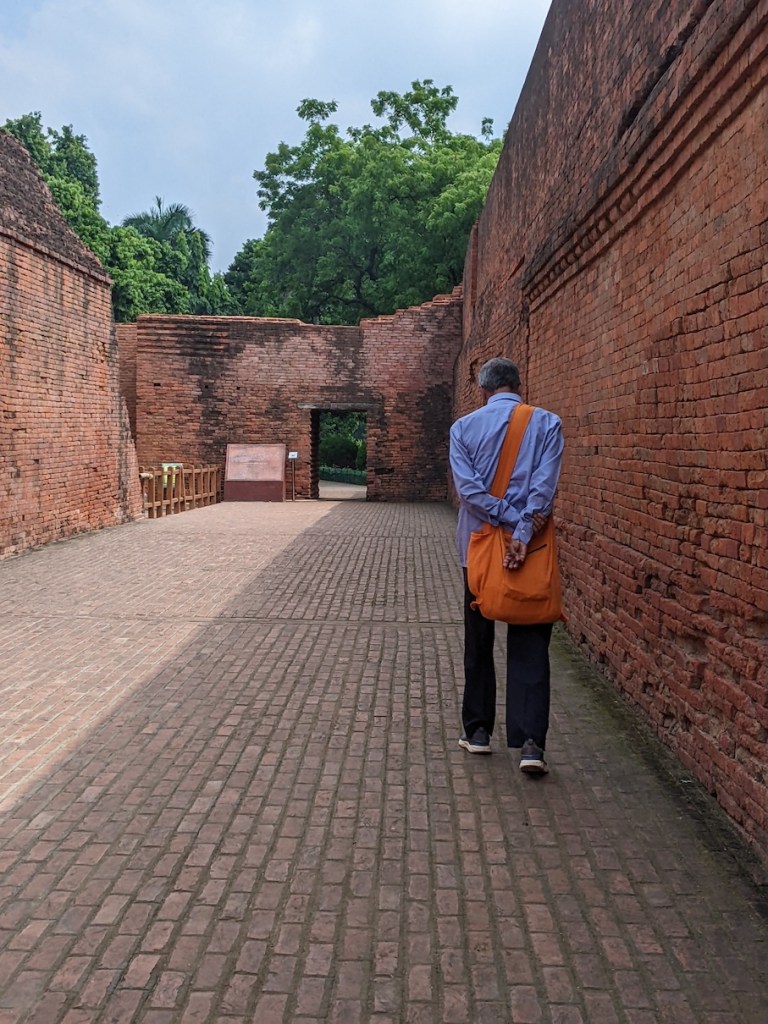

When we reached the Nalanda Archaeological Site, the place was almost empty. A few Buddhist monks walked quietly among the ruins. Otherwise, there was silence.

Red brick structures stretched out in long, orderly rows—monasteries, lecture halls, stupas, meditation spaces—all broken, and incomplete, yet still imposing. What we see today, historians say, is only a fraction of the original campus.

As I sat among the ruins, I tried to imagine this place as it once was.

Students debating ideas in courtyards. Teachers lecturing to hundreds at a time. Scholars arriving from distant lands, carrying manuscripts, questions, and curiosity. This was an epicenter of thought, of learning, of intellectual energy that actively shaped the world beyond India.

And then—ignorance, ambition, fear, agenda.

Someone decided it all needed to burn.

The tragedy of Nalanda isn’t just about destruction of buildings. It’s about how fragile civilization really is when power comes in the hands of the bigots.

A Missed Museum, A Quiet Exit

We wanted to visit the Nalanda site museum, which houses excavated sculptures, inscriptions, and artefacts—but unfortunately, it was closed for renovation when we were there.

So we started heading back.

By the time we reached Rajgir again, it was well past noon. The heat had become oppressive, and honestly, our enthusiasm to explore, having kids and seniors along with us, further had drained away. We briefly stopped at a hot spring area, where hot water came out of pipes…it did not feel natural….one could have as well kept geysers inside to supply hot water from those pipes. The atmosphere felt commercial and intrusive—priests asking for money, a general sense of discomfort. We didn’t stay long.

Lunch, however, turned out to be a pleasant surprise. We ate at a place called Punjabi Rasoi, and the food was tasty, hearty, and genuinely good.

From there, we drove straight back to Bodh Gaya.

Leaving Nalanda Behind

Nalanda isn’t a place you “enjoy” in the usual travel sense. It doesn’t entertain you. It doesn’t try to impress you.

Instead, it stays with you.

Long after you’ve left, it forces you to think—about knowledge, about intolerance, about how easily centuries of progress can be undone. Walking through Nalanda feels like standing inside a question humanity still hasn’t fully answered: How do we protect wisdom from ourselves?

If you ever find yourself in Bodh Gaya, do not skip Nalanda. Go slowly. Sit among the ruins. Let the silence speak.

Some places don’t tell stories loudly. Nalanda is such a place. It whispers however, if you can listen to it….

Leave a comment